High yield bonds are corporate bonds with speculative grade credit ratings, i.e., Ba or lower on Moody’s Investors Service’s scale and BB or lower on the scale employed by Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings. Because the press routinely derides these securities as “junk bonds,” one might infer that they are invariably obligations of dubious companies. In reality, high yield bond issuers include such prominent, long-established corporations as American Airlines, Ford Motor, Goodyear Tire, Nordstrom, Rolls-Royce, Uber Technologies, and Xerox.

The Argument for High Yield Investing

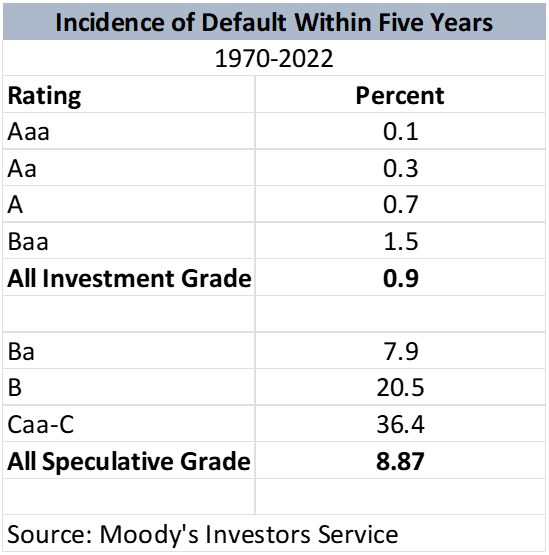

What does it mean, in investment terms, for a bond to have a low credit rating? As detailed in the following table, ratings deal in large part with default risk. A default occurs when a bond issuer fails to make a contractually promised interest or principal payment on schedule. Historical records show that the lower the rating, the higher is the probability that the bond will default over a stated period—five years, in the analysis at hand.

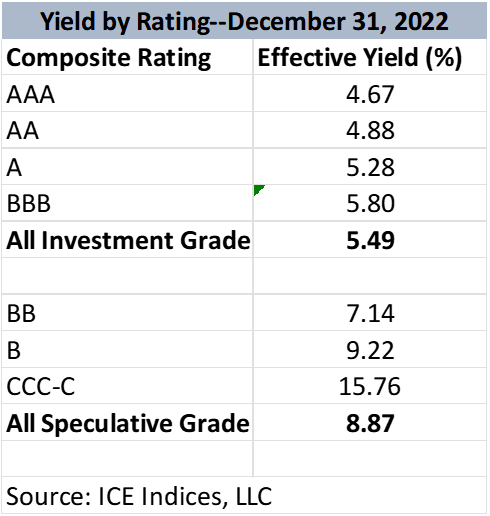

Why would you rationally choose to buy bonds with a comparatively high likelihood of inflicting principal losses, rather than stick to the safety of investment grade bonds? The next table below addresses that question. By accepting a greater risk of default, you obtain a higher yield on your investment.

On the date shown, high yield (speculative grade) bonds as a class yielded 3.38 percentage points more than investment grade bonds. That difference is known as the spread. It is usually expressed in terms of basis points, where one basis point equals 1/100 of a percentage point, meaning that in this instance the spread between investment grade and speculative grade bonds is 338 basis points. Note that spreads vary widely over time. One major reason why is that the default rate is higher in recessions than during economic expansions.

The basis premise of high yield investing is that by holding a diversified portfolio of high yield bonds, you can earn a higher net return than on high-quality bonds, provided the yield spread exceeds the expected default loss. Note that in most cases, bondholders do not lose 100% of their principal when a bond defaults, but instead emerge with some portion of their original investment, a percentage known as the recovery rate. Therefore:

Default Loss = Default Rate x (1 – Recovery Rate)

This simple formula would sum it all up if investors did not care about fluctuations over time in the value of their portfolios, which in reality they do. A high yield bond’s price may fall precipitously during a period in which its risk of default increases, even though no default actually occurs. Aside from demanding extra yield as compensation for high yield bonds’ comparatively high price volatility, investors expect to be compensated for the illiquidity of many speculative grade bonds. That is, many low-rated issues trade infrequently, meaning that they cannot be sold quickly by an investor who suddenly needs to raise cash.

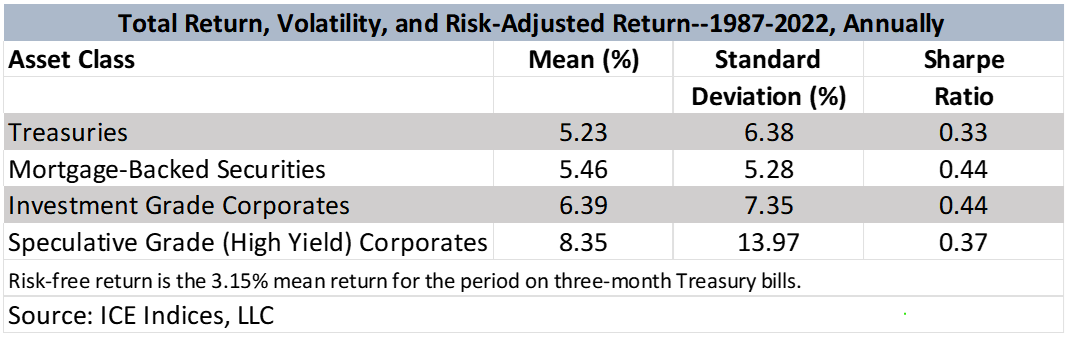

Considering these facts, and the solely prospective nature of yields and spreads, the question of whether high yield bonds represent a good investment over time is best gauged better by their actual, realized risk-adjusted returns. For two investments with equivalent returns, investors prefer the one with lesser risk. Modern Portfolio Theory defines risk as volatility. The Sharpe Ratio, which quantifies volatility by the statistical measure known as standard deviation, facilitates comparisons of investments with different historical rates of return:

Sharpe Ratio =

(Return of Asset Class – Risk-Free Return) ÷ Standard Deviation of Return of Asset Class

As detailed in the chart below, high yield corporates have the highest return among the four bond categories analyzed. They are also the most volatile and, on a risk-adjusted basis, are less attractive than either mortgage-backed securities or investment grade corporates. They compare favorably, however, with Treasuries.

The bottom line is that if you opt for maximizing yield, you should do it with your eyes open, undeluded by any notion that you are getting something for nothing. At times your paper losses will exceed those of more conservative investors who are willing to settle for a lower average annual return. You must decide, based on your own tolerance for risk, whether the extra return you can earn over time justifies the wider and more unnerving price swings you will experience along the way.

Self-Management versus Fund Ownership

As with stocks or investment grade corporates, you can create your own high yield portfolio, undertaking diligent bond-by-bond research. Note, however, that many high yield bonds are issued under Securities and Exchange Commission Rule 144a, meaning that they are targeted at institutional rather than individual investors. In addition, the round lot size in corporate bonds is $1 million, putting individual investors who trade in smaller amounts at some disadvantage in the form of odd-lot pricing differentials. A packaged product—an open-end mutual fund, closed-end fund, or exchange-traded fund—is an efficient means of acquiring a widely diversified high yield portfolio, supported by professional surveillance of bonds that can experience sudden, severe price swings.

The choices among packaged products do not include totally passive management (index funds). As noted above, many high yield bonds trade only occasionally. Holders of rarely traded issues with highly desirable characteristics (“museum pieces”) tend to be unwilling to sell except at prices well in excess of intrinsic value. Consequently, it is not feasible for a fund manager to replicate a high yield index by owning every single issue within it. As a practical matter, active management is the only available option.

Potential for Successful Active Management

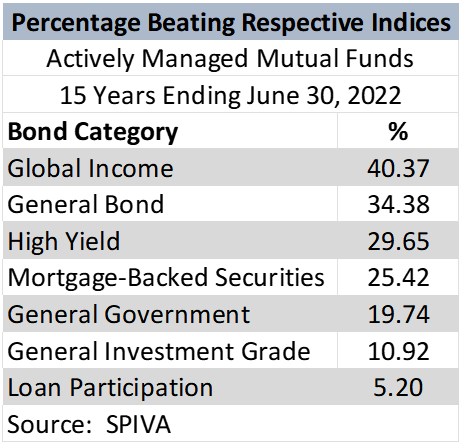

Whether you opt for fund ownership or the do-it-yourself approach, the high yield market is one in which active management has a comparatively strong chance of enhancing your returns. The chart below shows that over a long period, 30% of actively managed high yield mutual funds outperformed their benchmark. (SPIV, the source of the data, used the iBoxx $ Liquid High Yield Index as the benchmark.) By contrast, only 11% of actively managed investment grade mutual funds accomplished that feat.

The substantial difference in the incidence of outperformance between investment grade and speculative grade funds makes sense when you consider the much greater variability among speculative grade bonds, in terms of credit risk perceived by the market. For example, on March 31, 2023, 95% of the bonds in the ICE BofA US High Yield Index’s investment grade Composite Rating subcategory A1 (representing the strongest credits within the A category) and maturing in five years carried an effective yield in a range of 2.08 percentage points (4.10% to 6.18%). By contrast, capturing 95% of the bonds in the speculative grade B1 category and maturing in five years required a range of 7.43 percentage points (6.55% to 13.98%).

This comparison shows that quantitatively oriented measures such as credit ratings do not summarize the risk of speculative grade bonds as easily as with investment grade bonds. For high yield bonds, risk assessment and valuation involve considerable subjectivity, with the result that analysts’ opinions can vary widely. In such an environment, skill in sizing up credit risk can go a long way toward identifying bargains and ultimately producing superior returns. By the way, the yet higher percentages of global income and general bond mutual funds that beat their indexes may reflect more extensive opportunities in those categories to profit from astute top-down decisions involving reallocation among bond sectors.

The Low-Correlation Advantage

A final trait that makes it worthwhile to consider high yield bonds as part of an investment plan is the diversification benefit they can provide within a broader fixed income portfolio. Over the period 1987-2022, annual returns on Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities had a 91.8% correlation, based on ICE BofA indexes. As a rule, when one of those two categories had a bad year, so did the other. Investment grade bonds likewise had a fairly high correlation of annual returns with Treasuries, at 63.1%. Annual returns on high yield bonds, in contrast, had a negligible correlation of -0.6% with Treasuries.

In the most dramatic case, the ICE BofA US High Yield Index returned 57.51% as the U.S. emerged from the Great Recession in 2009, while the ICE BofA US Treasury Index returned -3.35%. That disparity reflected dissimilar impacts of a rebounding economy. When economic conditions improve, high yield bond prices rise to reflect declining default risk. Treasuries, on the other hand, can be hurt if increased demand for goods and services causes inflationary expectations to rise.

High yield bonds are by no means a perfect hedge for lower-risk bonds. In 2022, Treasuries and high yield bonds had abysmal returns of -12.86% and -11.22%, respectively. Over the long haul, though, high yield bonds can help to smooth out your performance as interest rates fluctuate and economic cycles unfold.

Conclusion

High yield bonds can be an effective vehicle for investors who seek high current income, provided they understand and are comfortable with the associated risks. They may either shoulder the task of selecting and monitoring their portfolios directly or delegate the responsibility to professional managers. Either way, rigorous credit analysis will be essential to their success.