The first difference investors are likely to notice between corporate bonds U.S. Treasury bonds is that the corporates yield more. For example, on June 30, 2022 the benchmark Treasury bond maturing in 10 years carried an effective yield of 2.97%. On that same date the median yield on issues within the ICE BofA US Corporate Index maturing in 2032 was 4.87%. (This index includes high- to medium-quality, or investment grade, issues.)

Subtracting the lower Treasury yield from the higher corporate yield produces a figure known as the yield premium or spread-versus-Treasuries (SVT). The spread is usually expressed in basis points, with each basis point equivalent to 1/100 of a percentage point. Thus, the June 30, 2022 SVT was:

4.87% – 2.97% = 1.90 percentage points or 190 basis points

Receiving more yield sounds good, but investors who choose corporates over Treasuries do not get something for nothing. The extra yield on the corporates represents a reward for taking greater risk. Two major risks that corporate bondholders incur are default risk and illiquidity risk.

Decomposing the Spread-versus-Treasuries

Although U.S. Treasury bonds are sometimes described as “risk-free,” that is not truly an accurate description. When you buy a Treasury bond you incur interest rate risk. If its yield rises, its price falls. This risk is not inconsequential, as Treasury bond yields fluctuate widely over long periods and vary even on an intra-day basis.

It is generally presumed, however, that you do not face any risk of a Treasury bond’s semiannual interest payments and principal repayment at maturity not being made in full and on schedule. Failure by a bond issuer to meet those obligations is termed a default. Notwithstanding periodic political showdowns over the debt ceiling and associated warnings that the United States could default for the first time ever, the market ordinarily assigns little if any likelihood to the possibility of that event ever coming to that pass.

Defaults can and do occur, however, within the universe of corporate bonds. Moody’s Investors Service reports that over the period 1970-2022, the incidence of default within one year for medium- to high-quality bond issuers such as those discussed in this article, was 0.1%, or one in 1,000. Over a 20-year period, the incidence increased to 5.3%, or about one in 20. As small as the likelihood is that you will buy an investment grade corporate bond and fail to receive scheduled interest and principal payments any time soon, the market awards you a yield premium over comparable-maturity Treasuries for taking that risk.

The default risk for which the market compensates you is a function not only of the probability of default, but of the expected loss in the event of default. Typically, bondholders do not lose their entire principal when an issue defaults. The default-related portion of a bond’s spread-versus-Treasuries is estimated as Probability of Default x (1 – Expected Percentage Recovery of Principal).

In addition to rewarding you for taking default risk, the market compensates you for the comparative illiquidity of your corporate issue. The market for U.S. Treasury obligations is widely regarded as the world’s deepest. Its issues change hands every day that the market is open. Bid and asked quotes for any Treasury bond you wish to buy or sell are readily available. The price at which the bond is offered will not be much above the price at which you can sell the bond. In contrast, many corporate bonds go days at a time without trading and the quotes on them show wide differences between the bid and asked prices. The market awards investors a yield premium as an offset to this lesser marketability vis-à-vis Treasuries.

Credit Ratings as an Investment Consideration

Because U.S. Treasury bonds are customarily seen as having a vanishingly small probability of default, they carry Moody’s highest credit rating, Aaa. The other most prominent credit rating firm, Standard & Poor’s, rates the United States slightly lower, at AA+ on its scale. Those ratings apply to all Treasury issues. Accordingly, when deciding which Treasury bond to buy, you can focus on which maturity date best matches your investment horizon, your outlook for interest rates (longer-maturity bonds generally fall more than shorter-maturity bonds when interest rates rise), and minor differences in marketability between the most actively trading bond of a given maturity and off-the-run issues with similar maturities. Those considerations also apply to corporate bonds; bonds that have smaller amounts outstanding generally are generally less liquid than larger issues. When buying corporate bonds, however, you also have to take into account variation in ratings.

The medium- to high-quality issues discussed in this article carry ratings in a range from Aaa to Baa (Moody’s) and AAA to BBB (Standard & Poor’s). The lower the rating, the higher is the rating agency’s estimate of the bond’s default risk. Your choice of which bond to buy involves a tradeoff between default risk and yield. You also need to take into account price risk; lower-rated bonds generally fall more sharply when recession fears escalate than higher-rated bonds with similar maturities, even in the absence of any defaults.

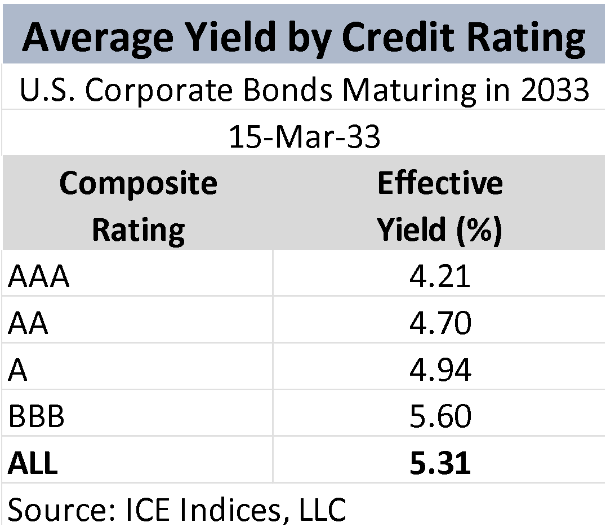

The table below shows average yields on bonds maturing in ten years, sorted by Composite Rating, the average of the ratings of the major credit rating agencies, as of March 31, 2023. Yield differentials among the rating categories vary over time, according to investors’ prevailing level of concern about default and price risk. An actively managed corporate bond portfolio may, for example, reallocate some capital from A issues to BBB issues at a time when the yield differential between those categories is unusually large by historical standards and, in the portfolio manager’s judgment, likely to decrease in the near term as the economic outlook improves, reducing investors’ concerns about default risk.

Note that rating differences do not explain all bond-to-bond yield differences within the corporate universe. Neither do all bonds of a given rating and maturity trade at or very close to the median yield. Industry classification is another important factor. For example, monthly and quarterly swings in oil and gas prices get reflected in the prices and yields of Energy bonds, but not in their ratings, which are intended to be longer-term assessments of default risk. In the Treasury market, on the other hand, there are no differences in ratings or industry classifications to contend with, as there is only one issuer. By contrast, 1,282 distinct issuers, scattered over 69 different industries, were represented in the ICE BofA US Corporate Index as of June 30, 2022.

Another Complication: Seniority

An additional selection factor in the corporate market that does not apply to the Treasury market is seniority within the capital structure. As noted above, bondholders usually recover some portion of their principal in the event of a default. The percentage of principal that they recover may not be identical on all of the issuer’s bonds, however. The company may have issued bonds with different priorities in principal recovery, designated (in descending order of expected percentage recovery in default) senior, subordinated, and junior subordinated. The company may have also given holders of one or more of its bonds a lien on certain properties. Those bonds, termed secured, would be expected to recover a higher percentage of principal in a default than the senior (unsecured) bonds. Generally, the lower an issue ranks in priority for principal recovery, the lower will be its rating and the higher will be its yield. Once again, choosing among specific issues entails a risk-reward tradeoff.

One Final Factor: Callability

If you buy a Treasury bond with a maturity date (for instance) 15 years from now, you can count on the bond remaining outstanding for that full period. That is an advantage if you expect interest rates to decline. You will have locked in the prevailing yield far into the future.

In contrast, some—not all—corporate bonds can be retired by the issuer at some point earlier than their maturity dates. For such issues, the company has an early redemption or call option. If interest rates decline, the issuer can exercise its option and replace the bond with a new issue that carries a lower interest rate. In such a case, you will not have locked in the prevailing yield through the maturity date. (Depending on the terms spelled out in the bond’s prospectus, you may receive a small premium to the principal amount in compensation for having the bond taken away from you.)

The market awards you extra yield for owning a bond that is at significant risk of being called, due to a drop in interest rates since the bond’s initial offering. Your choice between buying this bond, rather than a bullet-maturity (noncallable) alternative, represents one more risk-reward tradeoff.